Cellist Gives Mint Crowd Blast From the Past

- Share via

Early Monday evening, Bach barged past the bouncers at the Mint, a club on Pico, and once in, acted like he owned the joint. And for a couple of hours, he did, as Matt Haimovitz took over the bandstand, playing the first three of Bach’s six suites for solo cello. It was standing room only in the club, and the audience, even those quietly munching on hamburgers or salads, listened with rapt concentration.

That this revered, centuries-dead composer could sound more at home in a house of rock, blues and jazz than he does in many a concert hall or church is an eerie phenomenon, but not an inexplicable one. Bach did not write for the concert hall--there weren’t any in his day. His instrumental ensemble music was played either in the court or at Zimmermann’s coffeehouse in Leipzig; the solo pieces for violin, cello and harpsichord were mostly for private use in the home.

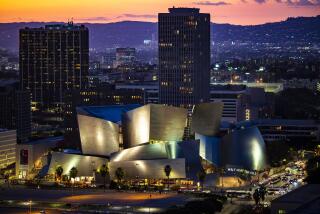

So my guess is that in its brief visit to the Mint, Bach’s ghost met with fewer surprises than it would have at the Music Center. The modern cello is a bolder, louder instrument than the one the composer knew, and the use of amplification could only have been a wonder to him. But given how he loved to pump up the volume on his organ music, these are things he surely would have embraced.

Nothing, on the other hand, would have been more familiar to Bach than music competing with conversation and food. If anything, he would have marveled at the respectful Monday night crowd--young and old. His biggest complaint might have been that the beer served in America is too weak.

Haimovitz played to the crowd and the setting, and that was another revelation of the evening. Experts in the historically correct approaches to early music tell us that Bach’s music sounded radically different than Haimovitz’s hyper-emotional, in-your-face approach. Certainly the thin-toned, 17th-century cellos with their cat-gut strings don’t inspire anything so robust as what this 31-year-old Israeli-born cellist achieves.

But what of the playing itself? Might not musicians in Bach’s day, and Bach himself, have been tempted to exaggerate in just the way that Haimovitz did in order to grab a restive audience’s attention?

In fact, the Mint offered the ideal opportunity for placing Bach in the real world.

Certainly there were disconnects in performing such intensely private music in such an exposed venue. But modern life is lived through disconnects, and Bach has little meaning for us if his music can’t function our way. What Haimovitz was able to prove is that timelessness in music doesn’t rely so much on historically re-creating the conditions of earlier times as it does in finding the appropriate up-to-date ones.

Playing in a club gave Haimovitz permission to go a little wild. He took liberties. They were imaginative, illuminating ones that reminded us what a fanciful improviser Bach was reputed to have been and how he constantly rethought his music and everyone else’s. One example was the pallid, otherworldly tone Haimovitz produced for the second Minuet of the Suite No. 1. Another was the weight, heavy as a thumping electric bass, with which he landed on the slow chords at the end of the Prelude to the Suite No. 2. Neither of these effects is on Haimovitz’ recent, enthralling recording of the Suites. They don’t belong there, but they did at the Mint.

After a brilliant beginning as a prodigy, which included a high-profile record contract with Deutsche Grammophon, Haimovitz is in the process of reinventing his career. He dropped out of concert life in the mid-1990s, just when he might have moved on to a new level of stardom, to attend Harvard and learn more of the world. Now he is back, brimming with fresh ideas. He has founded his own record label, Oxingale. His “Listening Room” tour is taking him around the country to play the Bach suites in pop clubs for very little money (tickets Monday were $15, the club seats only a couple hundred, and Haimovitz’s fee was a cut of the gate) but a great deal of glory.

In these experiments, Haimovitz has, indeed, recaptured the freshness in music making. There is nothing like the intimacy of hearing great music in a close, casual environment, and Monday night the cellist seemed to absorb as much energy from the crowd as we did from him. That pleasant smile he gave when a beeper went off during an especially intense moment was an acknowledgment that even the deepest sentiments must exist in an imperfect world.

Haimovitz’s set Monday was early, an opener for the more typical bands that appear at the Mint. After the Bach was over, the club returned to normal--it was louder, a bit more raucous, more of what it must have been like at Zimmermann’s. But magic had been in the air, and I think everyone understood it. Bach blessed the Mint.

More to Read

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.